Before you watch this video you should really check out the previous video in the Biostatistics & Epidemiology section which is an introduction to Bias & Validity. That video forms the foundations for this one.

Sampling Bias & Selection bias

Sampling Bias or Selection Bias is when selection of the study sample from the overall population is not random. This leads to a group of study participants that is not representative of the overall population and results that are not generalizable to the population (AKA Low external validity). A common example is when participants volunteer for a study (AKA Self-selection bias). In this case those that choose to volunteer are likely different from those that choose not to participate.

Confounding

Confounding is when the study results are distorted by some factor other than the variable(s) being studied. It appears that there is a relationship between the exposure and health outcome based on the results, but there is not really a relationship. Some factor other than what is being studied is distorting the results. A confounder is a characteristic is that is common to the exposure and the health outcome. Rather than A causing B, C is associated with A and B. In this example C is the confounder. If you removed C completely, A and B would not be associated. The problem with confounders is that an unwise researcher may come to the conclusion that there is causal relationship between the exposure and outcome if he or she does not recognize the confounder.

In research, you would ideally like to be able to show that your variable of interest caused the observed difference in outcomes. For example, you want to be able to show that your treatment leads to less cases of disease in the study population. If the treatment and placebo groups aren’t similar to begin with you can’t come to this conclusion. If the groups are different at the start of the study you can’t be sure if the observed differences at the end are due to your treatment or some sort of predisposing factor that was present to differing degrees in the study groups.

For example, you can’t learn much if the group receiving your treatment has an average age of 25 and the group receiving the placebo has an average age of 75. In this case, your results are being confounded by the difference in age.

Obviously, when you are creating a research study you want the different groups to be similar in age, gender, ethnic diversity, socio-economic factors and lifestyle factors. However, having groups that are similar in only these types of known prognostic variables is not enough. You also need the different groups to be similar in characteristics you aren’t even sure affect the disease process. There could be some type of risk factor that has not yet been identified as being pivotal to disease development. You want your groups to be similar with regard to this unknown factor too. How can you make two groups similar based on an infinite list of potentially important factors that haven’t even been identified yet? The answer is randomization.

Randomization

Randomization is just the process of selecting from a group in a fashion that makes all possibilities equally likely to be selected. To illustrate this point imagine you have a deck of playing cards. If you take a deck of cards straight out of the box and pick the top card you are not getting a random selection. It could be a new deck of cards in which the highest card is likely on top or you could have last played a game like solitaire that puts the cards in a particular order. However, if you shuffle the deck thoroughly before selecting the top card the chances of getting all the cards are equal. In research studies, randomization is like shuffling the patient’s before assigning them to different groups so each patient has an equal chance of being in the different groups.

The process of randomly assigning patients to different groups should give you comparable groups with regard to any known or unknown confounders. However, randomization won’t work as well with very small sample sizes, because chance will play a larger factor in determining the characteristics of each group.

When group assignment is not random baseline differences between groups can occur and there is an increased possibility of confounding. For example, if you allow for group assignment to be determined by personal preference, severity of disease, or day of the week your results could largely be explained by these differences in baseline characteristics. Assigning all patients that come in on a Thursday to one group and all patients that come in on a Saturday to the other is not randomization. You might get more unemployed patients on a week day or the weekend bus routes could limit some population’s ability to arrive on weekends.

Stratification

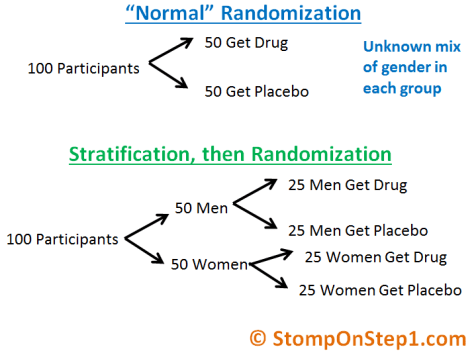

Sometimes randomization is not enough on its own. More often than not you will get an equal distribution between groups for characteristics such as gender, but there is still a chance that you will get more males than females in one group. This is especially true if the sample size is small. If you know that gender is an extremely important prognostic factor for your disease (like if you were studying the frequency of an X-linked genetic disease) you don’t want to take the chance that this could happen. The way to avoid this is called Stratification. In Stratification you first divide your population by a particular characteristic and then you randomize. You can think about stratification as randomization that is balanced with regard to one particularly important factor.

Blinding & Placebos

If a patient knows they are in the group that is not receiving the drug they might be less likely to be complaint with the prescribed regimen or they could be more likely to drop out of the study. There is also potentially a psychological effect of knowing that you are not receiving the “real” drug. If a patient knows they aren’t getting the drug they could lose hope and have higher stress. Therefore, which group a participant is in must not be known by the participant. This process of “hiding” which group a patient is in is called Blinding.

You also want the providers and research staff to not know which patients are in which group, because they could treat the groups differently based on that knowledge. For example, a provider may feel compelled to prescribe additional treatments to a patient receiving a placebo or could spend more time with patients receiving the real drug because they want the study to be successful. If the provider knows which group a patient is in they may also accidentally tip off the patient in which case the patient would no longer be blinded. A Double Blinded Study is where patients and providers are unaware of the patient’s group assignment. Sometimes you will see the term triple blinded which means some other group like data analyzers, technicians or other support staff are also blinded. Which group a patient is in should not be revealed until the very end of the study when you are analyzing data.

A Placebo is just a “drug” without an active ingredient that mimics the treatment it is being compared with. Placebos are given to the control group. If the treatment is a pill, the placebo should also be a pill that is the exact same size, color, and shape. The patient must not be able to be differentiated the placebo from the actual treatment to prevent “un-blinding.” By giving a patient a placebo, you are trying to give them “no drug” without them knowing. Patients receiving placebos can receive other forms of treatment, but they aren’t given the drug being studied.

CrossoverStudy

Crossover Studies are experimental studies that have the participants “switch groups” part way through the study. For example, patients that started with the placebo switch to getting the treatment halfway through the study while those that started with the treatment get the placebo after the halfway point. In this study design there is no separate control group as participants act as their own controls.

Now that you have finished this video you should really check out the next video in the Biostats & Epi section which covers different types of study design like Cohort, Case-Control, Meta-Analysis & Cross-Sectional.

Pictures Used: “Gold Dollar Coin” available at http://openclipart.org/detail/190431/gold-dollar-coin-by-casino-190431 under Public Domain Dedication

Nice Thanks a lot

Melvin Hernandez DMD

I am gratefull fore your efforts in teaching us

When it comes to blinding, double/triple blinding is to remove bias and not confounding, right? I got confused when you mentioned it’s eliminate confounding or bias